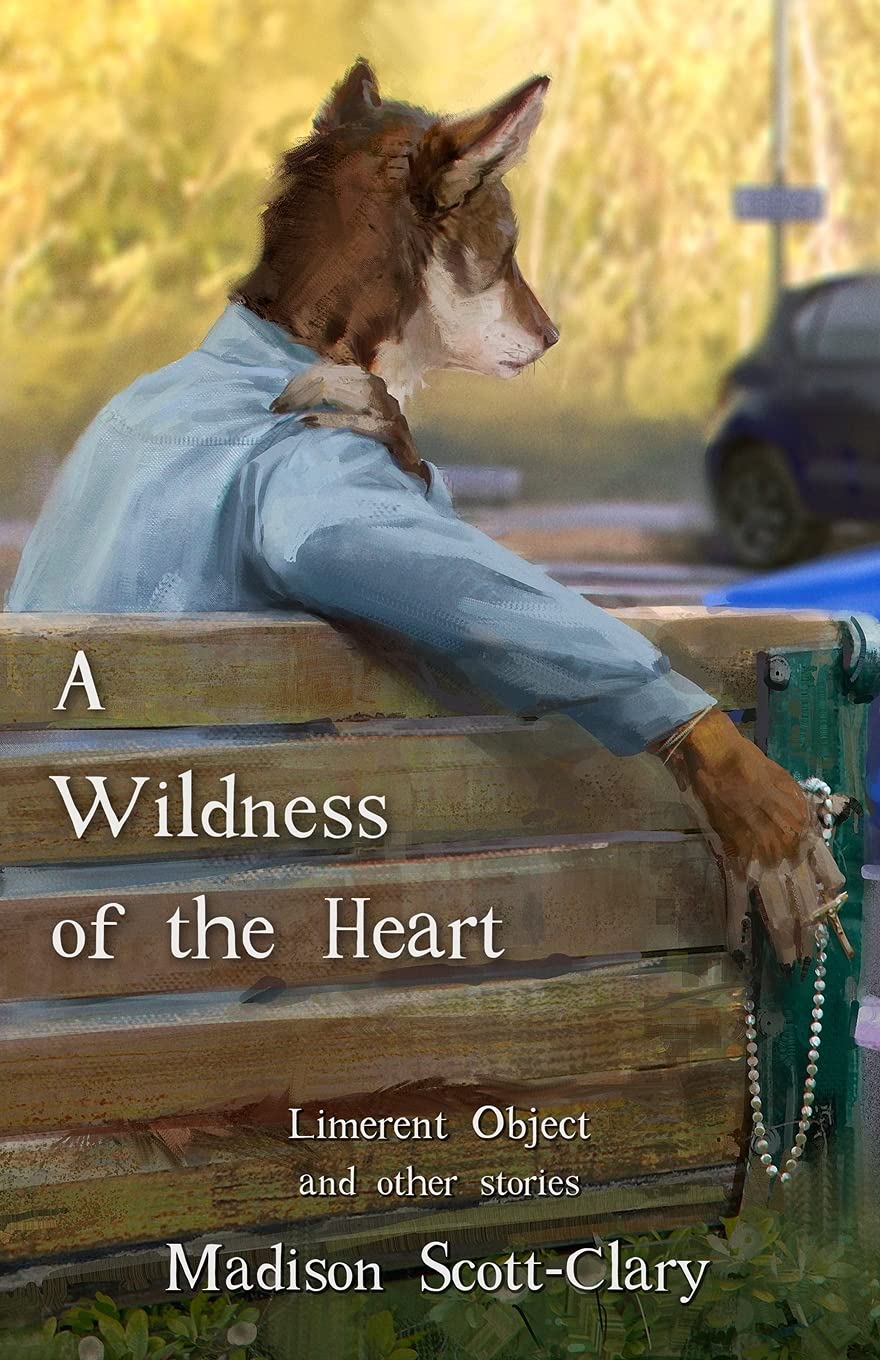

A Wildness of the Heart by Madison Scott-Clary

Review by Casimir Laski

Madison Scott-Clary’s A Wildness of the Heart is a collection of short stories bookending a single novella, Limerent Object, which comprises the vast majority of the length, and from which the title is derived. For those unfamiliar with anthropomorphic literature, these six stories fall into what is often referred to as the “Coffeeshop Fox” genre, where our otherwise-familiar world is populated by anthropomorphic animals. The central story will be the focus of my review for a number of reasons, not the least of which being the extent to which I personally connected with it.

Like many of the stories in this collection, Limerent Object follows a young adult in the small city of Sawtooth, Idaho grappling with romantic feelings—the protagonist in this case being Dee Kimana, a Catholic coyote on the autism spectrum, who left the seminary several years prior to pursue a career as a therapist despite remaining devout in his faith. As he begins to ponder more deeply his decision to abandon the priesthood, and more broadly ruminate on the process of discernment in his life, Dee comes to the realization that he is falling in love with his closest friend, Kay, whom he met at university, and with whom he remains in regular contact.

Now in his early thirties, Dee has moved beyond the burning years of adolescence to settle into a mostly comfortable, mostly stable professional existence, and yet he remains plagued by a nebulous, vestigial sense of youthful anxiety about his trajectory in life—about how he was able to make such an important decision on such short notice, and why said decision received no pushback from the church itself. The story is told primarily through entries in Dee’s journal, which he begins writing at the request of his own therapist (he mentions in an early footnote that “[He] wouldn’t trust any therapist who doesn’t have one.”), rounded out with the occasional relevant email or text conversation.

I will admit that the parallels between myself and the protagonist bordered on the uncanny at times, and certainly contributed to my avid investment. Like Dee, I both possess an intimate familiarity with Catholicism and have spent a great deal of time wrestling with the place of religion in the modern world, and share his introversion, general social awkwardness, and tendency to overthink things to the point of becoming mired in seemingly endless spirals of thought. Like Dee, I am both no stranger to grappling with complicated romantic feelings, and yet not particularly experienced in the field at large—and like Dee, I too have long struggled with the subject of discernment, only realizing most of the way through my own time at university that I was on the wrong path, and there of my own accord. Strangely enough, I even have a great interest in and fondness for the real-world counterparts of his species.

However, even those who cannot connect to Scott-Clary’s characters as directly should still be able to understand them thoroughly, and empathize with their experiences. The various tales of A Wildness of the Heart, diverse as they are, contain a refreshing degree of relatability, presenting slice-of-life stories that are as easy to fall into as they are likely to remain in the reader’s mind long after the final page has been finished, stories possessed of not only appeal beyond the traditional boundaries of anthropomorphic literature but the ability to speak more directly to real-world human experiences.

I have found that the best written stories invoke in me a peculiar, almost contradictory sense of investment: a hungering desire to learn what happens next contrasted starkly with an air of nervous tension, very nearly verging on dread, at the idea of it all going wrong. This can be said not only of highly speculative works, such as secondary-world fantasy or high-concept science fiction, but also of stories of a more down-to-earth variety, regardless of whether the stakes involve the survival of individual people, nations, or worlds, or something as mundane, in the grand scheme of things, as a relationship between two characters.

Limerent Object manages this balance of investment excellently, with Scott-Clary’s prose placing the reader into the mind of the anxious, pining coyote with an effortless grace. Not only was I able to quickly understand the protagonist’s dilemma and background through exposition that always felt natural and meaningful, but I remained thoroughly invested throughout the narrative, from the sessions Dee runs with his clients to the now-complicated conversations he fumbles through with the subject of his newfound affections, and from the coyote’s recounting of his own therapist’s advice to recollections of his time in first the seminary and later the public university where he met Kay.

The main criticism I have for the collection as a whole is that I feel the limited length of the other five short stories allows them little room to truly shine as the novella does. Given the strength of the latter, I have no doubt as to the author’s ability, but I cannot help but wish we as readers were given more time to get the know the characters that populate the stories bookending Limerent Object—those featured in Of Foxes and Milkshakes being a primary example. The snippet provided to us of the lives of the titular fox pair is endearing, and appears laden with potential that might bear much fruit in a longer story, including a more thorough exploration of their relationship in the vein of the novella that precedes it.

That being said, I would be remiss to deny that even in the shortest of Scott-Clary’s stories, her writing manages to bring a laudable level of humanity (if you’ll pardon the phrasing) to the animal characters whose lives we only so briefly get to glimpse. Throughout my reading the collection, I was stunned at just how real, just how thoroughly human the characters felt, leaving me half-expecting to pass some of them on the street in my own hometown. Even now, more than a week after reading Limerent Object, I find myself thinking on the relationship between Dee and Kay, hoping that things work out. Any writer capable of making their fiction seem so little like a mere invention of their own mind deserves recognition.

This leads me to what I consider to be the only other thing approaching “criticism” that I have for A Wildness of the Heart, one that I am not entirely sure is even fair to label as such. Both writers and readers of stories featuring anthropomorphic animals (and to a lesser degree, albeit similar manner, of speculative fiction at large) are likely familiar with a certain line of mainstream thought: that speculative fiction (i.e. fantasy, science fiction, supernatural horror, and furry fiction) somehow occupies a “lesser” status than realistic fiction by virtue of the liberties it takes with reality. This mindset seems to stem from an attitude about the “highest calling,” so to speak, of the arts: that if the purpose of any artform is to express some greater truth, then why bother with including speculative elements in the first place? Would these not merely “get in the way” of the “highest” forms of expression?

Some of this can be chalked up to gatekeeping and familiarity bias, much as it took some time for cinema to be widely considered a “proper” artform capable of merit and worthy of full-fledged academic criticism, or how a select few scholars had to fight for decades against entrenched attitudes for Tolkien’s fantastical works to be studied as serious literature. I myself have encountered this line of thinking as both a reader and writer, specifically regarding my interest in animal literature, which is often unfairly dismissed as either being simply made for children or otherwise incapable of profundity (if not both). I have always found these attitudes to be both frustrating and inaccurate, and so, much to my chagrin, I must admit that at times, I found myself wondering what the point of telling the stories of A Wildness of the Heart with anthropomorphic animals was—if perhaps these stories might have been better served by simply featuring real-life humans.

Certainly, when implemented with deliberation and purpose, speculative elements can go to great lengths to illustrate greater truths, infusing a story with rich symbolism and shepherding readers to consideration of otherwise familiar subject matter in a new light. With a novel like Watership Down, the epic, Odyssean nature of the plot and mortality-focused lapine cultural worldbuilding take on completely different dimensions by virtue of being told through the eyes of real-world rabbits in the contemporary English countryside, living in the shadow of modern man, much as Olaf Stapledon’s Sirius utilizes science-fiction elements to explore existentialism through the eyes of a genetically uplifted canine, or Georgi Vladimov’s Faithful Ruslan derives much of its allegorical power through the casting of a Soviet guard dog in the lead role. Works like Mannix’s The Fox and the Hound or London’s White Fang convey powerful themes through their brutal dedication to limiting the anthropomorphizing of their animal protagonists, while on the opposite end of the realism spectrum, fantasy novels such as Redwallpopulate their secondary worlds with anthropomorphic animals as a mirror to the trope of traditional humanoid fantasy species, and The Wind in the Willows imbues itself with a sort of whimsical, rustic English fairytale-like charm.

But to tell such grounded, such relatable, such fundamentally human stories with anthropomorphic animals will naturally invite questions as to the narrative purpose of this decision (and indeed, when I recommended this collection to friends outside of the fandom, it was one of the first points of discussion raised). I am well aware of the line of reasoning which argues that the use of anthropomorphic animals in such mundane, human situations serves to explore and challenge traditional conceptions of societal propriety in regards to mores, relationships, and identity—something that anyone familiar with the outsider-infused culture of the furry fandom will be no stranger to. Additionally, in the interest of fairness to all writers in the “Coffeeshop Fox” subcategory of furry fiction, an argument can be made that an appreciation of the “aesthetic,” so to speak, of anthropomorphic animals is justification enough for their inclusion in a story—that writers have no need to “justify” this element of their work beyond a desire to write that way, and that any demand to do so is nothing more than exclusionary, ivory-tower snobbery.

A Wildness of the Heart would undoubtedly have a broader appeal if it were simply told with human beings, and yet at the same time I must recognize that an artist who pursues popularity at the cost of vision will often end up with none of the latter, and a fleeting, guilt-laden helping of the former. I want to be clear that I ask these questions not to delegitimize furry fiction—quite the opposite, in fact. My reasoning is threefold: primarily because I know these questions will arise in more mainstream literary circles, secondarily because I believe this work is excellent for representing furry fiction to audiences outside the fandom (which would inevitably spark the aforementioned conversations, as it did within my own circle of friends), and tertiarily because I am genuinely unsure of what to make of my own thoughts on the matter.

One thing I can say for certain, however, is that Madison Scott-Clary’s beautiful collection was thoroughly worth my time, and I eagerly await her future forays into anthropomorphic slice-of-life fiction. A poignant reflection on the complicated feelings that nearly all people grapple with during at least some points in our lives, brimming with romantic passion and yet constructed with a mature restraint, and possessing a subtle intimacy that permeates nearly every page, A Wildness of the Heart manages something truly special with the deceptively brief glimpses it provides into the lives of its various characters—characters who will likely live on in the memory of readers long after the final page has been finished.