Review by Casimir Laski

Note: This review contains minor spoilers.

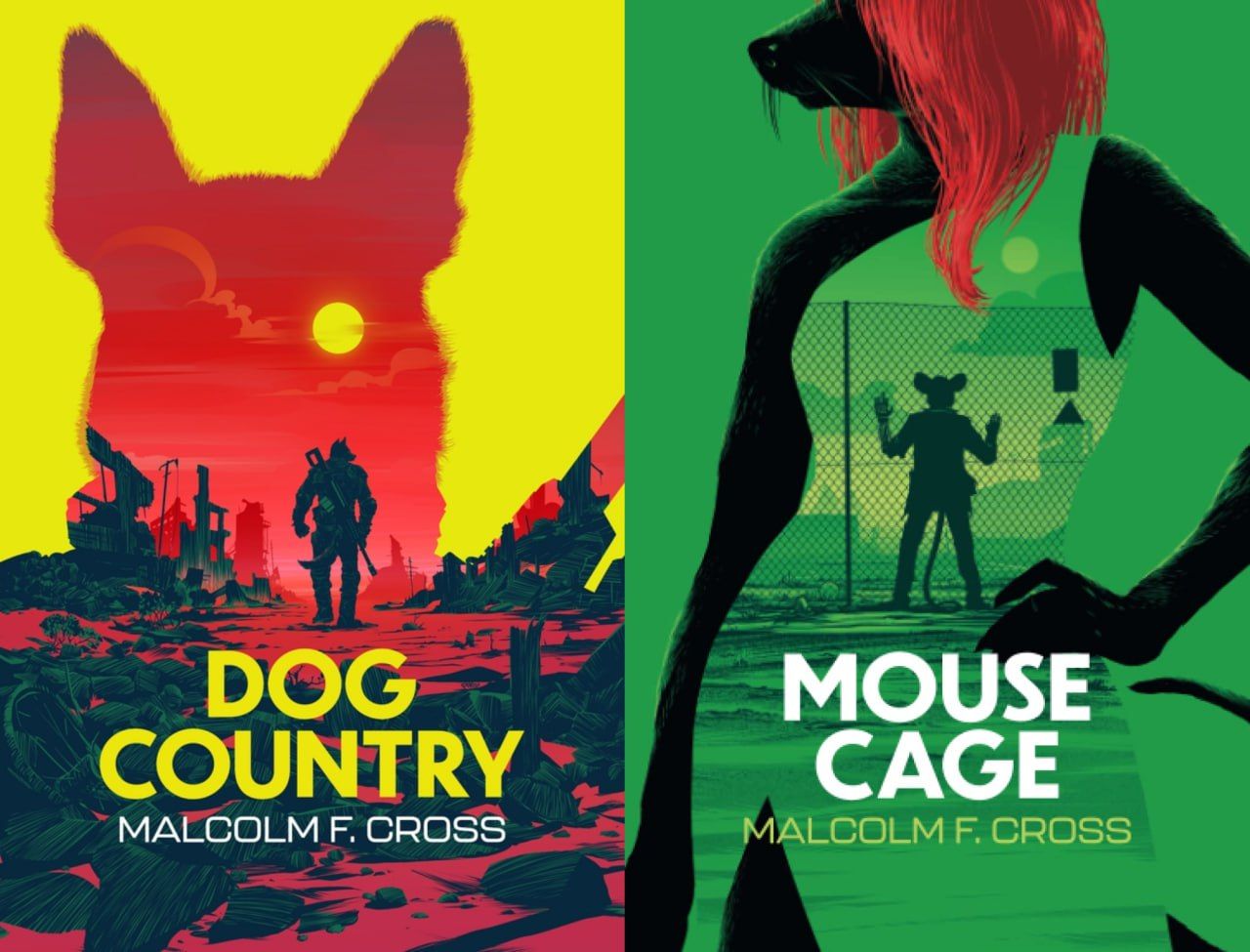

With Dog Country and Mouse Cage, author Malcolm F. Cross appears to have bridged quite an imposing literary gap: managing to write a pair of novels that are both undeniably “furry,” in so far as they fully utilize and explore their protagonists’ existence as anthropomorphic animals, and simultaneously feel at home amongst mainstream, contemporary, grounded science fiction. Given that the two books not only share their near-future setting but contain limited narrative overlap, and more broadly serve as thematic companion pieces to one another, I believe it is appropriate to review them together.

Dog Country and Mouse Cage belong firmly to what I term the “hybrid anthro” category of furry writing, arguably the most common type found in traditional speculative fiction, where anthropomorphic animals exist alongside ordinary humans in some variant of our world as a result of either magic, convergent evolution, or genetic engineering. Cross’ furries (the in-universe colloquialism favored over the politically correct “synthetic persons”) are a result of the latter. First developed in laboratories in the mid-to-late 21stCentury, various species were designed for different purposes by Estian Industries, only for the “Emancipation” to end their collective existence as corporate property and bestow upon them legal personhood.

Set primarily in the early years of the 22ndCentury, albeit told in not-entirely chronological order, in both works Cross hits the ground running with one of his strongest elements: his worldbuilding. Envisioning what human society might look like just shy of a century from now is no light undertaking, and obviously grants authors an imposing degree of leeway, but through what was either extremely thorough research and predictive consideration, or a string of damn good bluffs, the author constructs a setting that feels both disturbingly possible as a light-cyberpunk semi-dystopia, and yet unnervingly familiar to the present.

Vast swathes of Russia, Kazakhstan and China have been devastated in the “Eurasian War” of the 2060’s and 70’s; chemical, nuclear, and biological fallout from the conflict has further threatened the already precarious global ecosystem. From the ashes of failed states in equatorial South America, the Middle American Corporate Preserve operates as a late-capitalist nation-state and financial juggernaut with international reach. Drones and 3D-printing are ubiquitous, nuclear fusion appears on the cusp of being feasibly commercially utilized, fighting is dominated by electronic warfare, and advances in genetic engineering have trickled down to the lowest rungs of society.

But Cross doesn’t spell much of this out to the reader, instead leaving it to them to pick up the various puzzle pieces he scatters throughout his narratives and assemble them into a more coherent picture, an approach I personally find quite rewarding and engaging. Rather than point out what would to us be the eccentricities of his imagined future, he generally presents the speculative elements of his story as his characters see them in the course of their daily lives—including their status as genetically engineered, humanoid animals.

Which brings us to the first of the novels: Dog Country. Though sections of several chapters are told from the perspectives of a few of his clone brothers, the spotlight primarily falls on Edane Estian, a humanoid dog designed by Estian Industries for one purpose only: to be a soldier. The only problem is, after seven years of intensely disciplined upbringing, he was freed from the program, along with his brothers and all of the other genetically engineered “furries,” declared a legal person, and adopted by a human family in a process known as the “Emancipation.”

After a childhood of struggling to adapt to human norms, Edane enlisted with a private military corporation alongside a number of his brothers, serving briefly in Tajikistan during a period of unrest, only to be severely wounded in a suicide bombing shortly before the country descended into civil war. Now, living back in the comfortable suburbs of the MACP, Edane has a normal life: a steady girlfriend, Janine (a fellow furry, herself a humanoid thylacine), two loving adoptive mothers, and a place on a MilSim team that has a chance at going professional, playing a sort of augmented-reality infused, paintball/airsoft-style sports wargame. But in spite of all this, Edane still feels a vague longing for purpose, only exacerbated by the fact that he knows exactly what he was made to do: fight, and kill.

Now in his twenties, the dog soldier recognizes that this element of his nature should disturb him, that he should instead be contended with what he has—but, with the exception of his service in the Caucasus, ever since the Emancipation, Edane has never truly felt like he belonged. And so, when several of his brothers form a communally organized PMC and take on a contract to overthrown the repressive dictatorship of Azerbaijan, crowdfunded by the country’s own citizens, Edane is faced with a choice: does he linger in his current malaise in hopes that things will eventually settle, or embrace what he was literally born to do and rush halfway across the world into yet another warzone?

As mentioned before, the author’s constructed world of San Iadras (taking its name from the capital city of the MACP) is fully realized in ways that convincingly balance futuristic innovation with speculation drawn from current societal, political, and technological trajectories, rendering the setting itself as almost another character, complementing the human(oid) cast: always present and yet never intrusive, engaging without being distracting. The very concept of a civil war crowdfunded via the internet and boosted by social media may yet pan out, and feels right at home in the long tradition of science fiction authors making genuine, if often far-fetched at the time, predictions about the conjoined evolution of technology and broader human society.

Edane himself, while not a particularly complex character (intentionally so, given his artificial genetic coding and rigorously disciplined early life), proves to be a suitable vector for introducing readers to the 22ndCentury that Cross envisions. Additionally, it is easy to draw parallels to autism regarding the difficulties he faces in adapting to social norms that everyone around him just seems to naturally understand. I will admit that I found some of Edane’s central internal conflict to be underexplored, perhaps owing to the novel’s rather brisk pacing and length, but the supporting characters, some of whom receive perspective chapters or chapter-sections of their own, play off the protagonist, and round out the story’s cast, rather nicely.

While the neatly wrapped up ending arrives somewhat abruptly, the often-non-chronological chapter order may leave some readers confused (especially when diving into an already-unfamiliar setting), and the author’s prose occasionally features the missteps of a talented up-and-comer finding his footing (the novel having been self-published in 2016 before a 2020 re-editing), all in all, Dog Country is a solid military science fiction story, serving as a strong introduction to Malcolm Cross’ rich near-future setting, and comprising a fairly light read.

That is not in any way something that could be said of Mouse Cage. The second of Cross’ “San Iadras” novels is longer in word count, deeper in characterization, as well as narrative and thematic complexity, and far, far darker in terms of subject matter: Where Dog Country certainly contains its genre-standard moments of violence and gore, trauma and mourning, there are not-infrequent points in which Mouse Cage feels like the emotional equivalent of being forced to swallow broken glass—and given that I mean that as a compliment, I must elaborate.

Mouse Cage tells the story of Troy Salcedo, an anthropomorphic black-furred mouse created, like his twenty-three brothers, for laboratory research. Categorized by their human overseers as “Class-C specimens,” the two dozen clones were subjected to experiments with absolutely no ethical or legal restrictions—experiments which claimed three of the twenty-four brothers before Troy’s outbursts during a corporate audit resulted in the Emancipation.

At the beginning of this review, I described these novels as companion pieces, and in this, I cannot help but think of the contrast between Jack London’s two xenofiction masterpieces, The Call of the Wild and White Fang: the former involving a domestic dog going feral, and the latter a wild wolf becoming tame. But unlike in London’s most celebrated works, there is no moral equivocation here: The Estians of Dog Country, raised to be strong and capable, instilled with discipline and a sense of grander purpose, look on the Emancipation with emotions ranging from disillusion to outright despair, and, even once free, gravitate of their own volition towards the military service for which they were created. But for the surviving Salcedo brothers of Mouse Cage, the Emancipation quite literally saved their lives from an existence too horrifying for most people to comprehend, and yet, because of their traumatic experiences, despite their strenuous efforts to move on, in many ways they remain trapped years after they first emerged into the sunlight from the labs of Lake North. Edane pines for the security and certainty of doing exactly what he was created for; Troy spends his every waking moment desperately trying to forget that purpose.

The story begins with Troy delivering a speech at a benefit dinner for the foundation that supports his family, filling in for another of his clone brothers. Opening with a grim anecdote on the incinerator used to dispose of bodies in the lab, and describing how their “specimen classification” marked them as suitable for “testing” without any ethical restrictions, readers are given glimpses from the very first page that the confident façade Troy shows to his brothers and the world is just that. While far from the only one with even visible scars, he bears the most prominent mark of their shared past: a prosthetic arm, designed by his mechanically skilled brother Saigon. Plagued by recurring nightmares of his time in the labs of Lake North, most commonly involving the loss of his real left arm, which was surgically removed without anesthetic (save for that applied to his vocal cords, to mute his screaming), Troy is further burdened with overwhelming guilt over the part he was forced to play in experimenting on his brothers when the doctors used the exposed nerve endings of his arm to interface him with complex equipment.

Given that Troy was the clone most “favored” (if it could be called that) by the doctors when selecting “specimens” for assistance, and that it was his daring to speak up during a corporate audit that revealed the horrors of their treatment to the outside world, he has assumed the position of de facto “eldest” in the family—the one his brothers can always turn to when they need help, while, in his own mind, undeserving of being able to rely on them in turn. Of the twenty-four Salcedo brothers, three never made it out of the labs, and seven have died since—of disease, murder, accidents, and even suicide—each loss another crushing reminder of Troy’s own inadequacies.

And it is in this state, forced to relive a portion of his trauma in front of a selection of wealthy donors, that he meets Jennifer Dixon, a genetically engineered thylacine working various odd jobs, including as an erotic dancer. When their initial failed one-night stand leads to a deeper form of intimacy, the two enter into an openly on-again, off-again relationship punctuated by lavishly detailed sexual encounters—an arrangement Troy finds it increasingly difficult to live with the more he falls in love with her, even as she refuses to utter those same words back to him.

Mouse Cage manages to be a surprising number of things in the course of its lengthy and somewhat meandering-by-design narrative, often at the same time: an erotic romance burning with passion, and a tragic exploration of a toxic relationship between two uniquely damaged partners who nonetheless derive crucial support from one another; a gut-wrenching account of survivor’s guilt and a tragic slice-of-life family drama; a science-fiction thriller and a social commentary piece; a globe-trotting dystopian adventure tale and a grueling account of an addict relapsing under pressure. And, perhaps even more surprisingly, it manages to be all of these rather remarkably well, while never feeling exploitative or sensationalist in even its bleakest and most harrowing moments.

In the course of Troy and Jennifer’s tangled romance, Cross takes his readers from the glistening high-rises of uptown San Iadras to the slums of Del Cora, and from the University of Minnesota’s nuclear reactor, where Troy works on his doctoral dissertation, to the wastelands of post-apocalyptic Central Asia, aiding refugees and collecting samples of the ravaged environment. However, this novel is not what I would consider “plot-driven,” as these various locales serve far more as backdrops for the true story.

Instead, it is Tory’s personal journey that remains the central focus, and Malcolm Cross fully delivers when it comes to providing readers with a richly layered, deeply flawed, and yet irresistibly sympathetic hero, regardless of what the character in question would think of the term being applied to him. This is not to say that the events of the story play no part in his development, but rather that he himself possesses enough substance to retain the audience’s investment: Through the ups and downs of his confusing relationship with Jennifer; doctoral research in nuclear physics and ordinary life on the streets of San Iadras. Through the turmoil of depression and bitter guilt over what was done to him, what he did to survive, and what he failed to do for his brothers, driving him into the abyss of despair and relapse. Through persistent nightmares that leave him barely able to function, and waking flashbacks of both his hellish years in the lab, and his dearly bought freedom in a Catholic orphanage under the tutelage of the benevolent Padre Muñez, who adopted the surviving twenty-one brothers when no other humans would. Through all of this, Troy Salcedo comes across as a shockingly, often disturbingly, authentic and relatable portrayal of the human condition.

His brothers—each named after a different city—round out the effect brilliantly. Dallas, who affects a down-to-earth demeanor and distracts himself with scientific fascinations while secretly shouldering the same trauma as his brothers; Philadelphia, the corporate-government ladder-climber who thinks the world of Troy despite knowing his flaws better than anyone else, and abandoned his academic pursuits to find a job that would allow him to covertly support their family financially; Florence, a teacher who fears ostracization by his brothers on account of being gay, struggling to reconcile this with both his religious upbringing post-Emancipation, and the way his attempts to find genuine romantic companionship are hindered by his prospective partners’ frequent fetishization of his status as a genetically engineered animal.

As would be expected from any large family, the Salcedos have their own complex internal dynamics, with certain brothers sticking together in twos or threes as other pairs clash over differences of personality, while others still remain aloof. Not only do they feel like people individually, but like a family when taken collectively, and their mutual love is palpable, shining beautifully through even the darkest stretches of the story: always providing support for one another regarding employment and living situations, education and healthcare; ever watchful for warning signs of depression and suicidal ideation, and just making themselves available when another finds himself in need of someone to talk to or lean on—even when Troy steadfastly believes he does not deserve it.

At the core of both of Cross’ novels lies a question that anthropomorphic fiction is in many ways uniquely suited to grapple with: what exactly does it mean to be a “person”? Dog Country certainly engages with this subject, but never with the incisive immediacy that Mouse Cage does—and this brings me back to something I mentioned in the opening. I have read my fair share of furry fiction, produced both within and without the fandom, that features characters so fully realized that they feel “authentically human,” but I have never seen it handled quite in the way Malcolm Cross manages. Madison Scott-Clary’s A Wildness of the Heart, like many stories in the “coffeshop fox” subgenre of furry fiction, uses its excellently characterized anthropomorphic cast as stand-ins for humanity, their “furriness” having more impact as metacommentary than within the text; meanwhile, a novel like Jonathan Edward Durham’s Winterset Hollow, despite placing fascinatingly written anthropomorphic animals into our real world, remains told from the perspective of the humans who encounter them. But Mouse Cage fully commits to exploring the existence of a genetically engineered animal living in a human-dominated world, that, although set eight decades in the future, is a strong reflection of our own.

Tying into characterization, the author’s dialogue often contains an intentional clunky awkwardness, punctuated by evocative depictions of body language, going to great lengths to imitate real, unscripted conversations, and show, rather than tell, what his characters are thinking and feeling. Beyond this, Cross’ general prose, already strong in the first San Iadras novel, sees steady improvement here as well, though there are a handful of phrases, especially for certain gestures and quirks, that are reused excessively. On a related note, some portions of the novel, specifically involving Troy’s strained relationship and deep-seated sense of self-loathing, do at times seem a bit repetitive—though I must both acknowledge that this is part of the package deal when writing a story involving battling with addiction and severe trauma, and admit my sympathies in knowing how difficult it can be to balance portraying repetitive behavior without one’s writing itself seeming repetitive. At the risk of sounding slightly puritanical, some of the sex scenes come across as rather gratuitous, though again, it could be argued that this is part of the point, helping readers to experience the euphoric highs and devastating lows of the protagonist’s life. I also have a sneaking suspicion that Jennifer, and her tumultuous relationship with Troy, will be contentious among readers—much as it is among Troy’s own brothers—but I’ll leave others to come to their own conclusions.

As a character study, Mouse Cage takes a mildly unorthodox structure regarding plotting: In the manner of real life, sometimes things will simply not work out, with plot threads cut short as a sudden development shifts the narrative focus, or the characters come up against an obstacle too imposing, and are left with no choice but to pack their bags and move on. (Though, given that in the author’s note, Cross expresses interest in continuing Troy’s story, I retain hope for a certain world-renowned physicist to be taken down a peg, but I digress). There aren’t even any proper overarching antagonists—or, perhaps more accurately, the novel’s only true villains last personally interacted with the rest of the cast nearly two decades before the point at which readers enter the narrative, even as the marks of their torment linger. Likewise, it is hard to pinpoint one particular climax, though two heartbreaking conversations near the end come to mind as contenders—the latter involving a beautifully cathartic informal confession with Padre Muñez. (Despite only being directly featured a handful of times, mostly in flashbacks, the Dominican friar who raised the Salcedos as an adoptive father is easily the standout human character.)

Though in my estimation, Dog Country stands in the shadow of Mouse Cage, the former nonetheless serves as a solid point of entry to Malcolm F. Cross’ highly inventive setting, one that should entice fans of both science fiction and furry literature, while setting the stage nicely for the more visceral experience of its follow-up. And though I have to warn prospective readers that the latter will (or at the very least should) disturb you—will often times throughout its course leave you sick to your stomach and with an aching in your heart—I must add that the ending, although hardly the stuff of fairytales, does feel like several breaths of fresh morning air after a long, dark night.