Review by Casimir Laski

While in this review, I will be focusing on two of his novels, what initially brought Michael H. Payne’s writing to my attention was a pair of short stories from the FurPlanet line of anthologies: “Emergency Maintenance,” featured in the science fiction collection The Furry Future, and “To Drive the Cold Winter Away,” from the cross-genre, adventure-focused Exploring New Places. Both showcase the author’s signature strengths, featuring richly constructed settings brimming with life of their own, thoroughly developed characters who, despite containing an authentic degree of complexity, always remain delightfully endearing and remarkably easy to root for, and graceful prose that never overstays its welcome.

(To briefly tangent, “Emergency Maintenance” is described in its introduction as being an entry in Payne’s still as-of-yet-unfinished anthology novel A Meadow in the Mist, a book that I would greatly love to see published.) But all of this is to say that, if anyone out there finds themselves enticed to give the two novels I will discuss here a read, I urge you not to stop at the bounds of Payne’s longer-form work.

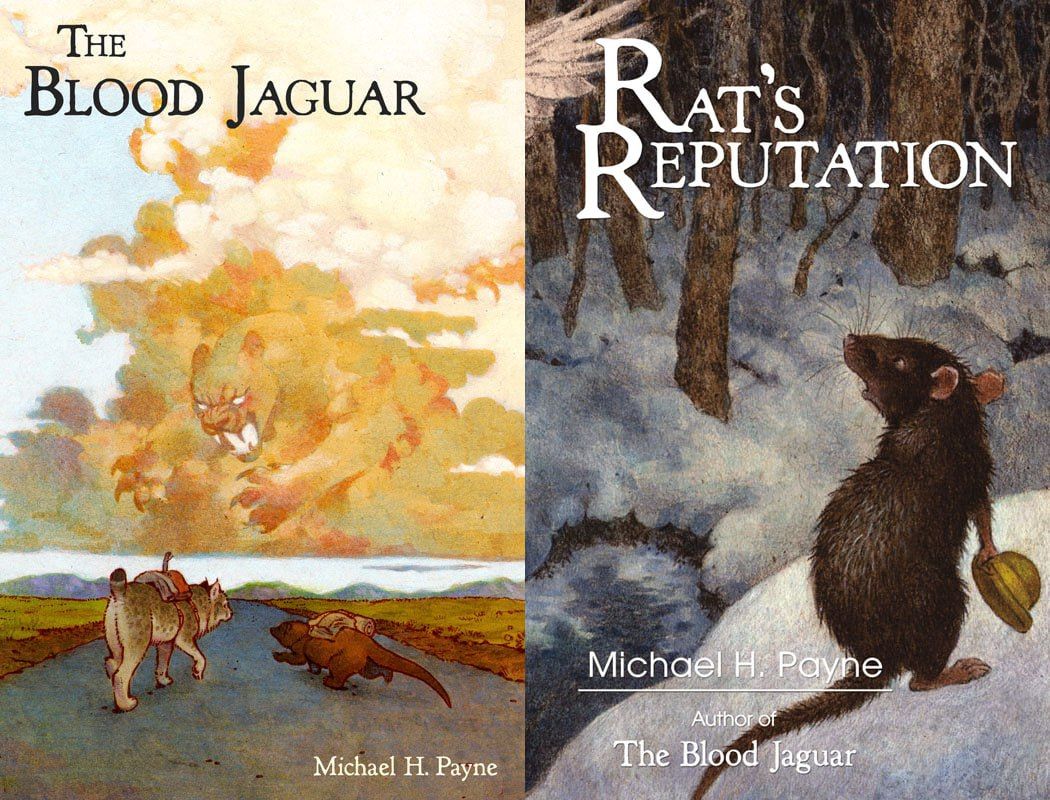

The Blood Jaguar and Rat’s Reputation both take place in the same constructed setting, a world highly reminiscent of late-19th- and early-20th-Century works such as The Wind in the Willows or The Hollow Tree Snowed-In Book—and possessed of a great deal of the same rustic charm, albeit with modernized (and therefore broadened) cultural and geographic horizons. Payne’s animal characters inhabit the same middle ground of anthropomorphism as Grahame’s Ratty and Toad: not quite so limited as the physically realistic rabbits of Watership Down, and yet not quite as human as the cast of Beastars.

In The Blood Jaguar, we begin on the outskirts of the town of Ottersgate, following Bobcat, a former wanderer who has managed to put down tenuous roots, and has partially succeeded in escaping a reputation for delinquency and catnip addiction. After a surreal encounter with a terrifying figure from the myths he never before took seriously, Bobcat seeks out the help of his neighbor Skink, an erudite, if unadventurous lizard, and Fisher, the local community shaman.

The latter pair soon discern that the three, collectively, have drawn the attention of the Curials, the twelve deities who supposedly govern creation, and become entangled in the latest occurrence of a (capitally rendered) Cyclical Myth. Setting out to both stay ahead of the Blood Jaguar, the renegade 13thCurial prophesized to unleash a devastating worldwide plague, as well as to determine what exactly it is that the gods have planned for them, the trio venture across the continent, braving forests and deserts, outwitting mercurial monarchs and conniving cultists—and, naturally, leaning more about themselves and each other in the process.

Bobcat serves as a well-executed, if not particularly groundbreaking, example of the reluctant hero archetype: a lazy, mildly hedonistic lay-about dragged into the limelight by the “call to adventure,” who is forced to gradually accept responsibility in pursuit of what forces beyond his control have decided is his destiny. The crafty, world-wise Fisher helps (and struggles) to provide him with guidance along the way, while the mild-mannered, academically inclined Skink is both thrilled and terrified to find himself living through stories he has thus far only been able to study from the comfort of his home. Their endearing, semi-dysfunctional three-way dynamic adds an additional layer of engagement to the immersive animal world and the author’s consistently high-quality prose.

Strange as this may sound, in some ways Payne’s approach reminds me of Tolkien’s The Hobbit, which—and this may be easy for contemporary audiences to forget, given the book’s place as one of the cornerstones of modern fantasy—was decidedly unorthodox for its time, being essentially a pastiche of Beowulfwith a timid, middleclass early-20thCentury Englishman thrust into the protagonist’s role.

For as much as he draws on longstanding literary traditions and influences, be they the works of Kenneth Grahame or ancient myths from cultures around the world, Payne makes a conscious effort to add to the canon rather than merely retread old ground. The Blood Jaguar is both a classic, Campbellian “hero’s journey” tale, and simultaneously a reflection on the component pieces of that very narrative structure, on how the stories we tell shape us, and how our lives, in turn, shape them. Not particularly bright or clever, even by his own admission, Bobcat’s stumbling attempts to understand Fisher and Skink’s metatextual musings on the nature of storytelling, after finding themselves inhabiting such a tale, ultimately come together in a poignant, revelatory climax.

Rat’s Reputation, meanwhile, spans a much longer period of time—several decades, compared to its predecessor’s little over a month—and takes a much looser approach to plotting. The hero of this tale is Rat, also known as “Ratayo,” or simply “Tayo,” who was found alone as an infant in the wilderness, delivered into the care of a wandering squirrel caravan by one of the Curials. However, finding himself the constant target of ridicule and suspicion on account of his status as an outsider, he is soon handed over to one of the prominent mouse families of Ottersgate.

From here, readers follow the course of Rat’s life through the trials of adolescence and early adulthood, as he finds himself embroiled in juvenile rivalries and longstanding feuds, friendships and crushes, childish pranks and more weighty run-ins with the law—and while this does eventually entail some globe-trotting across the setting we were introduced to in The Blood Jaguar, Rat’s Reputation trades the looming threat of apocalypse for a far more subdued, introspective tale about belonging and identity.

At one and the same time, Payne draws more heavily on the style and tone of The Wind in the Willows while exploring the perspective of “outcast” species in a way that Grahame’s novels, with their simplistically villainous weasels and stoats, never bothered to. Rounding out the cast, all three of the heroes from the prior novel make appearances, helping greatly, though in very different ways, to shape the course of Rat’s journey. Here, the Fisher from The Blood Jaguar is simply Blaze, daughter of the current Ottersgate shaman, hungry for experience with the Curials; the younger Bobcat, still in the throes of addiction, is far more vindictive and prone to violence than the mellow character Rat helps him become. Skink, meanwhile, remains much the same, offering our protagonist much-needed companionship when his troubles with his adoptive community drive him into semi-self-imposed exile in the surrounding woods.

With its focus on community and belonging comes an expansive cast of characters, allowing Payne to play to another of his strengths, for with the inhabitants of Ottersgate, the author captures the spirit of small-town solidarity in all its forms: from the hospitable and supportive to the insular and provincial. One would be hard-pressed not to grow attached to Raymon, the elderly head of the Nibbler clan who advocates for Rat’s adoption, or Kily, a young mouse in his newfound family, with whom childhood friendship eventually blossoms into an endearing romance. But even those who most frequently clash with Rat nonetheless come across as authentically realized individuals, from the scheming Aunt Mileen, determined to usurp Raymon’s role and correct what she sees as the errors of his stewardship of their clan, to Corin Spinner, the entitled, but ultimately good-hearted, daughter of their family’s rivals. A personal favorite is Officer Hawk, one of the chief constables of the town: initially highly prejudiced and presented as rather one-dimensional, the gruff raptor’s relationship with the protagonist gradually thaws as the two come to properly know one another.

Additionally, in Rat’s Reputation, Payne doubles down on the metatextual elements of the novel’s precursor. Over the course of his life, Rat finds himself the subject of a great deal of stories, often (but not always) drawn from the truth, then enlivened with exaggerations for good or ill. This eventually makes him into a sort of Reynardian trickster character, derided as a crude, barbarous villain by certain residents of Ottersgate, and lauded by others as a sly rascal with a heart of gold. Excerpts from these tales, as well as poems and even the occasional academic (or pseudo-academic) work on Rat’s life, serve as epigraphs before each chapter, giving further insight into how our protagonist is viewed by the various communities that he never seems to fit in with—and further exploring the nature and impact of storytelling as an artform, and its central place in culture.

As I alluded to earlier, Rat’s Reputationis far more character-driven and far less narratively focused than The Blood Jaguar, with the five sections, titled “Rebirth,” “Raising,” “Roaming,” “Reckoning,” and “Resolution,” often serving more as loose collections of chronologically occurring vignettes—and yet, while both novels are certainly well worth the read, I found Rat’s journey of personal growth, and his search for a community where he can finally belong, to be the more moving of the two tales. However, it should be noted that, by introducing both the setting and several important figures in Rat’s life, the first novel lays important groundwork for its successor, even if both remain standalone stories inhabiting the same wider world. Honoring the legacy of The Wind in the Willows while adding his own unique blend of charm and wit, Payne’s delightful little duology serves as a welcome addition to the anthropomorphic canon.