Review by Nathan Hopp

It is the Meiji era in Japan. In a small town called Furusato, an older tanuki named Jiroh Kaze is establishing his new business in the red-light district. It is called a kagema, or a brothel that specializes in servicing men who have sex with other men. As he struggles to think of a name, a surprise arrives at his doorstep one rainy day in the form of a baby blue rabbit left abandoned by his mother. Jiroh takes pity on the orphaned baby and names his adopted son ‘Ameya’, subsequently naming his kagema the ‘Ameyashiki’.

Twenty years later, the Ameyashiki has become a thriving business, while Ameya has grown up into a kind and friendly, yet lonesome bunny who hates how he is treated by Furusato’s residents, most of whom look down on the lad for his assumed homosexuality. He cannot even form friendships with others his age out of fear of being bullied—this despite the fact Ameya only cleans up messy rooms and assists the dozen other Ameyashiki workers who have become close family to the blue bunny.

However, this all changes one day when he accidentally encounters a red she-wolf his age in a hilariously anime-like manner. Her name is Haru, and she moved into Furusato with her adopted porcupine father—Takumi, a former ninja assassin—in order to open up a family-run sushi restaurant. The rest of the book becomes a historical slice-of-life journey following Ameya’s life as he tries to find the bravery to explain his adopted father’s business to the wolf girl, forms a unique relationship with her, gradually learns about the scarred backstories of his adopted Ameyashiki brothers, and the looming threat of a local yakuza boss who is threatening both the kagema and Haru’s father’s sushi shop.

Here are two historical tidbits to keep in mind when reading Kageichi Kagi’s debut novel, “Change in the Midnight Rain”: Before the Meiji Restoration, most of the Empire of Japan was de facto ruled by various feudal warlords who hired honorable samurai to protect their lands. However, to make a long story short, their services were no longer needed once the new emperor assumed the throne, which meant that samurai and ninja like Takumi had become the equivalent of wartime veterans who couldn’t return to the battlefield despite wanting to.

Second, and most importantly, homosexuality throughout Meiji-era Japan (basically, from the late 1800s to 1912) was very much tolerated amongst commoners. Not accepted or rejected but tolerated. Samurai were sometimes even known to have male apprentices who also served as their lovers. Male prostitution also didn’t have as much of a legal stigma. Of course, these social attitudes started to gradually change the more Western influences and philosophy remained in Japan, but this tolerance was very noticeable throughout the reign of Emperor Meiji.

Even without already knowing such historical facts ahead of time, “Change in the Midnight Rain” provides a neat perspective of its world through the rare lens of a location in Japan not as explored as often. Not too many anime out there will focus on the wholesome exploits of a gay brothel, will they?

The Ameyashiki itself feels like its own enriched character with a friendly, accommodating atmosphere, serving as a sanctuary for its workers who want to let go of their tragic pasts, and the customers who want to either experience male companionship, or simply fulfill the carnal desires only a kagema can sate.

Everyone within the story feels real. They sound like memorably genuine people who lived in that period of history. Ameya himself is a very identifiable and likable protagonist. He does love Jiroh and the workers who serve as older brother and even mother figures to him. However, the reader easily sympathizes towards him for the way Furusato treats him as ‘the kagema brat’, which is why the bunny’s hesitation about telling Haru everything about his ‘family’, while selfish, is still very understandable (try casually telling a new friend, “My Dad owns a gay brothel that I grew up in.”). One other unique element about Ameya is his openness towards sexuality, specifically his preference for both men and women that could have been explored further.

Meanwhile, Haru stands out as a well-written female character in a story of mostly gay characters. Most female characters in gay-oriented fiction don’t have as much complexity or agency, often only serving as just the emotional support for the protagonist, yet Haru isn’t the case here. She’s extremely polite, firmly honorable to a fault, doesn’t tolerate being pushed around, and is easily impressed and open-minded. The backstory she shares with her adopted father could also serve as the plot of another book. Much like Ameya, though, she isn’t just a stoic, angsty protagonist. Both can be happy, they can be empathetic, they can be emotional, easily frustrated, curious, even lustful.

Besides character development and worldbuilding, one of Kageichi Kagi’s greatest strengths as a writer is how he utilizes classic cliches from Japanese storytelling, particularly in anime. “Change in the Midnight Rain” has tons of beloved anime tropes such as the badass female fighter, half-doting/half-overprotective parents, brooding characters with a past, colorful hair (or in this case fur), one cool sword, valuing love and friendship, a hot spring and, of course, plenty of yaoi fanservice. Kagi even somehow manages to take bad cliches and spin them to suit the story, one prime example being the first and second times that Ameya and Haru meet each other, and a certain very disliked trope often seen in comedic anime is played with. Or rather, the ideal scenario of said trope is used in a realistic, effective way. Even the plotline of Ameya keeping his kagema roots a secret from Haru isn’t dragged out as you’d expect, with the rest of the story focusing on their relationship, plus the interconnected pasts and relationships of others.

Unfortunately, the book’s one aspect that will divide readers is how flashbacks are formatted into the novel. Traditionally, at least in most Western books, if the story has multiple point-of-view characters, the narrative will have entire scenes set in the past be written into italics. It’s the same with what a character thinks, to help stand out from dialogue or what the narrator says. For the case of “Change in the Midnight Rain”, a flashback scene or chapter will start out italicized but then somewhere switch back to a de-italicized lettering. Sometimes, it can even start out de-italicized but switch back and forth until the narrative returns to the present. I’m unsure if this is a practice in Japanese literature, but for a Western reader, this formatting will confuse them at first.

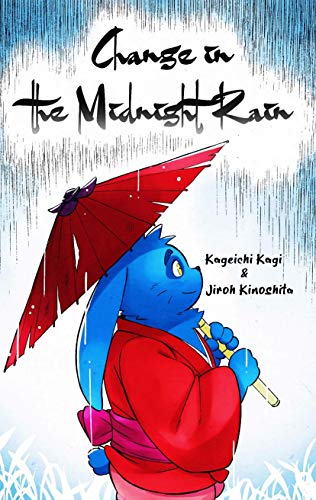

However, while this may temporarily pull the reader out of the story, this does not mean they shouldn’t read this beautifully crafted novel. Kageichi Kagi’s great writing and Jiroh Kinoshita’s fantastical cover art and interior illustrations will draw in lovers of historical and erotic fiction. It has a balanced diet of relatable humor and drama, intimate sex scenes, a range of relationships that have sincere chemistry, a laidback plot that can be as unpredictable as it is wholesome and a cast of character who are incredibly likable. It is a great combination that would be a wonderful thing to watch should it miraculously be adapted into an adult anime.

Overall, “Change in the Midnight Rain” is a delightful experience about love, familial bonds, and Eastern storytelling meeting Western storytelling. It reminds us that family isn’t about whose blood you carry, to never forget who you are, to take pride in what shaped you as a person, and that love comes in all shapes and forms.